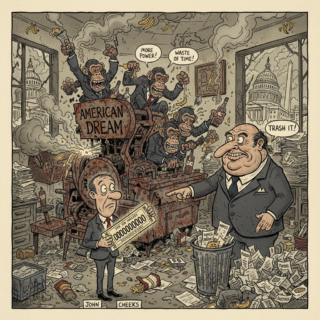

Some nights you can still feel the ragged edges of the American Dream tearing apart at the seams. You can hear the high, lonesome scream of it if you just turn off the television, kill the lights, and listen to the hum of the refrigerator. It’s a sound of pure, distilled desperation. Out here in the sprawling, manicured wilderness of the suburbs, we pretend that sound is just the wind in the trees or a coyote howling at a blood moon, but we know. We know it’s the sound of a man running out of road.

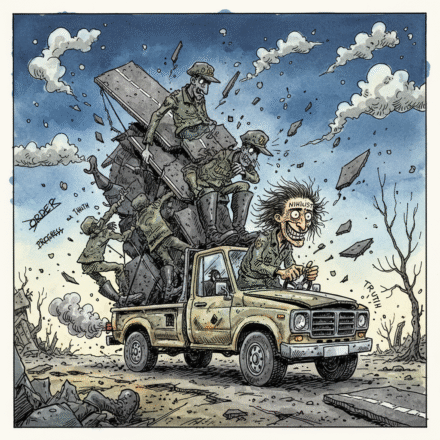

I was three sheets to the wind, wrestling with the ghost of a deadline and a bottle of cheap bourbon, when the police scanners started chattering like caffeinated squirrels. It’s a hobby of mine, a little peek behind the curtain of civilized society. Most nights it’s just fender benders and teenagers hotboxing their mom’s minivan behind the Piggly Wiggly. But not this night. This night had a different energy, a frantic, jagged pulse that spoke of something coming ‘off the rails’.

Faking It: An Inmate’s Mad Dash from Institutional Despair

The story, when it filtered through the static, was a thing of beautiful, tragic absurdity. A poor bastard named Timothy Shane, inmate at the local correctional facility, had decided he’d had enough of the grey walls and the tin-pot tyranny of the guards. So, he plays the suicide card—a classic gambit, a real Hail Mary of institutional despair. They ship him to the hospital, a place of supposed healing, and in a moment of choreographed chaos, he vanishes. Slips the shackles, ghosts out the door, and dives headfirst into the great American night.

This is where the story should get good, right? A modern-day Dillinger on a savage journey to freedom. But this isn’t the 1930s. There are no dusty backroads to salvation. There’s just an endless labyrinth of cul-de-sacs and two-car garages. Shane jacked a car, then another, a handgun reportedly vanishing from one of them into the ether—a Chekhov’s gun for a play that would never be performed. He was a phantom with a stolen pistol, a walking headline, a man whose options were evaporating with every mile marker he blew past.

Forty-Eight Hours of Fury: A Fugitive’s Suburban Labyrinth

He ran for two days. Imagine that. Forty-eight hours of pure, uncut adrenaline and terror, the world blurring past your window, every pair of headlights a potential cage. He was running from the bars, yes, but he was also running from himself, from a life that had cornered him so completely that faking his own death seemed like a reasonable career move. This was not a bid for freedom; it was the final, spastic death twitch of it.

And where did this ‘wild ride’ end? Not in a hail of bullets on the Mexican border. Not in a blaze of glory. It ended on a porch in Newton County. My God, the sheer, exquisite poetry of it. It ended in the belly of the beast he was trying to escape: the quiet, paranoid heart of suburbia.

Picture the scene. Two in the goddamn morning. The only light is the cold, accusatory glare of a motion-sensor floodlight. The air is thick with the scent of fertilizer and existential dread. And there’s Timothy Shane, the escaped convict, the desperate man, standing on the welcome mat of a perfect stranger named Audrey Flournoy.

He doesn’t kick the door in. He doesn’t brandish the missing pistol. He rings the doorbell.

And in that moment, the whole sorry saga transcends simple crime reporting and becomes a piece of high art, a perfect encapsulation of our deranged, technologically-mediated age. Because he’s not talking to a person. He’s talking to a plastic box with a fish-eye lens. He’s auditioning for his freedom to a doorbell camera.

“Hey…” he says, his voice a ragged plea beamed to a smartphone on a nightstand somewhere inside. “I’ve been out in the woods hunting, ending up getting lost for like five hours.”

‘Hunting’. Jesus wept. Here is a man being hunted by every cop in three counties, and his cover story is that he’s the hunter. The irony is so thick you could slice it with a knife. He’s a ghost at the gates, begging for sanctuary from a disembodied voice that is both everywhere and nowhere. He just needs a drink, he says. He’s got money, he says. He’s trying to perform a pantomime of normalcy for an unblinking digital eye, a last-ditch effort to pretend he’s just some good old boy who took a wrong turn, and not a man whose life has completely cratered.

And the voice from the speaker, calm and protected by layers of drywall and Wi-Fi, says what we all say when the darkness comes knocking. “No, I’m not opening the door. No, no sir.”

The Doorbell Confession: Surveillance, Society, and the Suburban Cage

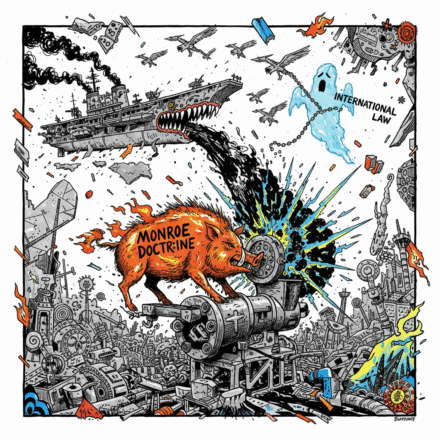

There it is. The death of the American dream, captured in glorious 1080p. We’ve built these fortresses of solitude, these smart homes with their digital moats, not to keep the monsters out, but to keep our own terrified humanity in. We’ve replaced community with convenience, and conversation with surveillance. Shane wasn’t just rejected by a homeowner; he was rejected by the algorithm. His story didn’t compute. Access denied.

They found him later, holed up in an abandoned house, the “lost hunter” finally tracked and trapped. The chase was over. The weird energy bled out of the scanner and it was back to cats in trees and stolen lawn gnomes. But the image of that man on the porch, pleading his case to a machine, will stick with me. It was more than just a crime story. It was a deep dive into our own bizarre reality—a world where a man can run for his life and find his last hope is a conversation with a doorbell, only to be told that no one is home. And in a way, he’s right. Nobody is.

Leave a Comment